Summary

Emergency Operations Centers (EOCs) play a critical role in supporting, and sometimes managing, incidents of various types, sizes, and complexity by bringing people together from various government, non-government organizations, and other stakeholder groups to support the needs of the impacted community through a coordinated response and recovery to the emergency. EOCs, to be effective, must facilitate the flow of resources and information across these various organizational lines.

Note, many jurisdictions are using different terminology such as Emergency Coordination Center (ECC). For our purposes, we are going to simply use EOC to describe a centralized location for emergency response and recovery support operations when activated.

EOC structures have never been standardized in the United States. As a result, these structures vary widely. In a past effort to look at how best to apply the Incident Command System (ICS) in EOCs, we looked at 185 different EOC org charts. The main take away was that no two EOCs were alike. Some EOCs are designed to support multiple disciplines in a single jurisdiction, and some support a single discipline across multiple jurisdictions. Some operate under a “pure ICS” structure while others use Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) or departmental structures. Others are hybrids of one or all three versions.

Given that EOCs operate under varying local government or organizational authorities, and may have varying missions, EOC are bound to be different. The question is: “Which EOC structure is best?”.

But first, let us ask if EOCs must be “NIMS-compliant”.

About NIMS/ICS

The National Incident Management System (NIMS), which includes the Incident Command System (ICS), was mandated by the U.S. government after the terrorist attacks of 9/11/2001 through Homeland Security Presidential Directive 5, which directed first responders to “enhance the ability of the United States to manage domestic incidents by establishing a single, comprehensive national incident management system.” This “mandate” was made effective by requiring that local, state, tribal and territorial jurisdictions adopt NIMS in order to receive federal Preparedness Grants. Almost all government jurisdictions participate in the annual Homeland Security Grant Program and are, in effect, required to adopt NIMS. In the mid-2000s, many jurisdictions, in an effort to become “NIMS-compliant” began to use ICS or ICS-like structures in emergency management as well as other first responder disciplines.

Once ICS training was readily available, NIMS/ICS was adopted as part of the national approach to emergency operations. As a result, many emergency management programs (EMPs) began to use ICS in the EOC, albeit in their own unique ways.

In the 20 years since, we have found that the ICS organizational structure can work well in the EOC, but it works best with some adaptation. And, while it helps to use ICS in the EOC as it is closely aligned with on-scene incident management as used in the Incident Command Post (ICP), ICS needs to be adapted for the EOC functions as the EOC typically supports, but does not command operations in most cases. The notable exception to this is when there are large, jurisdiction-wide incidents (such as hurricanes, mass care incidents, and snowstorms, for example) where there is not an ICP, the EOC may function as an ICP or Area Command facility and be responsible for tactical operations in the field as well as strategy and operations.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has promoted NIMS/ICS as a common, interoperable approach to sharing resources, coordinating and managing incidents, and communicating information during emergencies. The National Incident Management System (NIMS) defines this comprehensive approach and includes ICS as a system for managing incidents. NIMS recognizes that EOCs are part of framework for incident management as described in the Command and Coordination component of the National Incident Management System (NIMS). However, FEMA has struggled with how best to use ICS in an EOC. After an aborted attempt to develop ”ICS for EOCs” FEMA’s recent NIMS update identified three common ways of organizing EOC teams:

- ICS Structure: Many jurisdictions/organizations use the standard ICS organizational structure, either “Pure-ICS” (exactly as it is performed in the field operations) or “Adapted-ICS” (with some modifications for EOC operations). Pros: The ICS structure is familiar and it aligns with the on-scene incident organization. These structures can expand to include various branches and units that focus on specific activities or like-kind services. Cons: Some EOCs find ICS cumbersome and difficult to understand and resist adopting it fully. If an ICP is used, there can be confusion on who manages tactical operations.

- Incident Support Model: ISM reorganizes some of the major ICS-centered functions removing two functions from the Planning Section, situational awareness, and resource tracking. Situational Awareness is established as a separate section in this model. This structure puts the EOC Manager or Director in direct contact with the Situational Awareness and Information Management teams and it is designed to streamline resource sourcing, ordering, and tracking. Pros: This structure designed to focus on what is important in an EOC as opposed to a field organization. If done correctly, this model allows for the most robust Situational Awareness methodology. Cons: ICS purists resist this as they find this confusing. Also, it may not work well in larger incidents where the EOC is more of an ICP.

- Departmental Structure: This structure uses the day-to-day departmental/agency structure. This is perhaps the oldest EOC structure as its pre-dates ICS and was used during the Civil Defense era. This was used before many organizations changed to ICS structures and simply involved bring in department representatives to coordinate with their home department in supporting incident requirements. Pros: This structure requires minimal preparation or training for department representatives – they simply come in and do their normal jobs. Cons: While many of the departmental functions will bear a similarity to relevant ESFs, there are often required EOC functions that might not align with a particular department or with just one department. Department reps may think “we do not do that in our department” but there are often tasks that are needed even when not clearly aligned with a department.

Function-Based Structure

One structure that FEMA did not include in the list of EOC organizational options is the function-based structure that evolved during the early days of the transition from Civil Defense to Emergency Management. Sometimes referred to as the Functional Management structure, this structure uses Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) as its basis but can be put into an ICS structure. This model is normally intended to be flexible regarding the number of positions and organization to address each community’s specific needs. For example, if a community has a local library or community college that play important roles in the community, a functional management organization can fit the library or community college into the organizational structure. Many of the functions will bear a similarity to relevant ESFs.

Federal ESF Structure

In the mid 1980’s, federal planning efforts were directed towards a decentralized response for the first 30 days of the disaster. Federal departments and agencies were to undertake their responsibilities by function (eventually termed Emergency Support Functions). Plans identified lead and support agencies by function. Eventually the ESF structure was incorporated into the Federal Response Plan (FRP).

The federal ESF structure was more fully developed through the National Response Framework (NRF) which identifies ESFs that align to federal agency support functions. Federal ESFs provide the structure for coordinating federal interagency support for a federal response to an incident when this support is needed and authorized, both for declared disasters and emergencies under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Stafford Act) and for non-Stafford Act incidents.

State ESF Structure

Many states followed the federal lead identifying similar ESFs as the structure for organizing and coordinating state resources by function. While this helps aligns state and federal efforts this structure was never prescribed as an organizational concept for states to use; however, this structure was embraced by may state emergency management agencies.

Local ESF Structure

Many local governments have followed the state ESF structure for alignment, often adding ESFs for local activities not included in the federal model. Local governments often find that the ESF structure helps the EOC organize to effectively ensure delivery of needed assistance and resources to impacted communities. ESFs are often grouped within the ICS structure as described below.

Hybrid ICS/ESF Structure

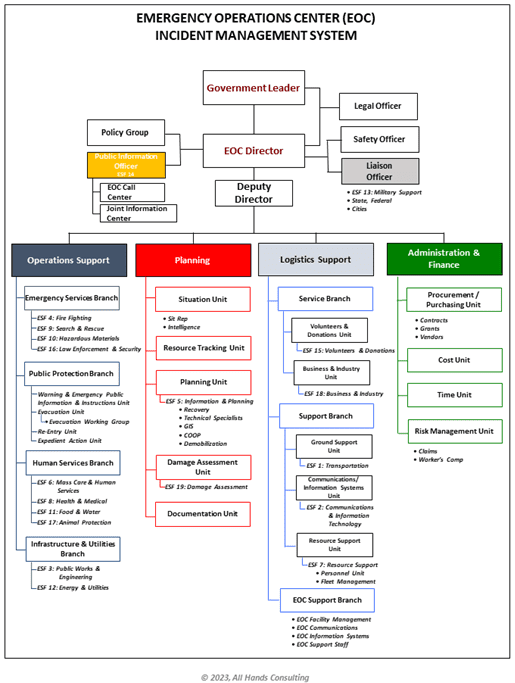

Based on mandates to adopt ICS, many state and local EOCs developed a hybrid ICS/ESF structure. The ESF structure is often used under an ICS foundation as shown in the example organizational chart below. This structure incorporates ESFs and other functions within the ICS structure of sections, branches, and units. This can be done on a modular basis with a flexible number of positions to address each community’s specific needs. For example, if a community has a local library or community college that plays an important role in the community, a functional management organization can fit the library or community college into the organizational structure.

Which Structure is Best?

There has been a lot of discussions in the EM community recently about what type of EOC organization is best. Clearly, the answer is what works best for your jurisdiction. In our experience the EOC/ESF Hybrid works well in large, robust organizations but not for smaller organizations.

Figure 1, Example Hybrid ICA/ESF EOC Organization

Conclusion

It is important to remember that whatever the organizational structure, the EOC should be a modular design capable of supporting a wide array of incidents. EOCs often utilize the NIMS/ICS management modular organization characteristics, developing structures that can be expanded as needed based on the incident and adapting to the differences between a specific localized incident scene (mass casualty incident, fire, etc.) or a jurisdiction-wide incident (flooding, hurricane, etc.).

Organization of the EOC staff can vary based on:

- The jurisdictional/organizational structure

- Local authorities and political considerations

- EMA staffing and EOC staffing availability

- The variety of stakeholder organizations participating

- The EOC facility limitations in terms of size, configuration, and number of seats

- The EOC capabilities for virtual operations (telecommunication options)

- The prevalent local hazards (hurricane vs. hazmat response)

Note that many incidents are short-lived and may not need the EOC to be activated. However, EMA staff and EOC support team members can help other first responder organizations in various ways.

The authors admit that they like the ICS/ESF structure as that is what they have been supporting for 20 years. However, we recognize that a new generation of emergency managers are now on board and are looking for improved organizations and operations. We welcome this and hope to continue to support the conversation going forward and hope to expand the conversation as to the pros and cons of each based on real-world experience.

One bit of data that would be useful in this effort is to understand the current situation. So, we ask:

What are the most common ways of organizing Emergency Operation Centers?